The light meter can be a most perplexing part of the camera to master. Amateurs and professionals alike struggle at times to establish correct exposure in complex lighting situations.

The most traditional way to use our built in light meter, is to simply point the lens at the subject and then choosing an aperture and shutter combination until "correct exposure" is determined. However this seemingly simply technique of aim-your camera-and-trust-the-meter method rarely satisfies the discerning photographer.

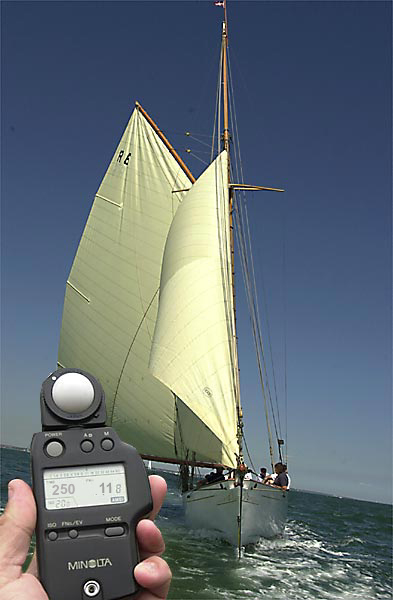

When a complex lighting situation arises, as with these photographs, (large areas of bright light, in the sea and sky) we often need to find a different approach to insure we achieve correct exposure.

We know the importance of not dramatically overexposing and losing detail in the highlights, in this case the sails. We also have to watch out not to underexpose and lose detail in our shadow areas. This is likely to happen in these types of situations, as the built in light meter will "see" large amounts of light reflecting from the sea and sky, and ask you to give less exposure than is really required thus resulting in underexposure, (silhouetted sailboats in extreme cases.)